Economic & Market Overview - August

Global

At the end of July, the US Federal Reserve has cut interest rates for the first time in more than a decade and signalled its readiness to provide more support as growth slows in the world’s largest economy. In a move that may have been influenced by political pressure, the US central bank cut its key benchmark interest rate by a quarter of a percentage point, to a range of 2% from 2.25%. This is the first reduction in borrowing costs since immediately after the financial crisis a decade ago. In his statement, the Fed chairman, Jerome Powell, indicated that it was weak global growth and the US-China trade war that swung the scales in favour of a rate cut. The US Labour market remains strong with the lowest unemployment rate since the late 1960s, and various other economic indicators points to a robust US economy.

President Trump criticised the extent of the cut when he tweeted: “What the market wanted to hear from Jay Powell and the Federal Reserve was that this was the beginning of a lengthy and aggressive rate-cutting cycle which would keep pace with China, the European Union and other countries around the world. As usual, Powell let us down, but at least he is ending quantitative tightening, which shouldn’t have started in the first place – no inflation. We are winning anyway, but I am certainly not getting much help from the Federal Reserve!”

This battle between the Federal Reserve and Trump is far from over as the President embarks on his 2020 re-election campaign, which will no doubt rest heavily on US economic growth (fuelled by lower rates and a potentially weaker dollar).

The Trump administration re-ignited the trade war with China as it extended tariffs on a further $300 billion of Chinese goods from September. Global stock markets and emerging market currencies reacted negatively to this news, causing a very bumpy start to August.

Across the pond, the new leaders of the European Central Bank and European Commission were announced. Ursula van der Leyden is a protegee of German Chancellor Angela Merkel and has been appointed as the new president of the European Commission. France’s Christine Lagarde takes over from Mario Draghi as president of the European Central Bank. She was France's first female minister of finance, the first woman to head the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the first woman to head a large American law firm. Market commentators view her appointment as a dovish move with Lagarde likely to retain a low interest rate policy for the foreseeable future.

Boris Johnson, not surprisingly, was elected as the new leader of the Conservative Party in the United Kingdom and by default, became the new prime minister. The next three months will be dominated by his efforts to re-negotiate the current Brexit deal, and failing that, the possibility of a no-deal Brexit.

The International Monetary Fund released its July World Economic Outlook where it forecasted 3.2% global growth for 2019, lifting to 3.5% in 2020. Risks to these estimates are, however, mainly to the downside. They include further trade and technology tensions that dent sentiment and slow investment; a protracted increase in risk aversion that exposes the financial vulnerabilities continuing to accumulate after years of low interest rates; and mounting disinflationary pressures that increase debt service difficulties, constrain monetary policy space to counter downturns, and make adverse shocks more persistent than normal.

Investment against this backdrop remains challenging as neither global equities nor bonds provide particularly attractive opportunities this late in the economic cycle. Diversification is probably the best strategy against the surprises that the rest of the year may hold.

South Africa

As was widely expected, the South African Reserve Bank lowered the repo rate by 25 basis points. This reverses their move in November 2018 when the rate was increased by 25 basis points. Given South Africa’s ever-growing debt servicing burden households, businesses and government, it brings some relief but not nearly enough to kickstart the faltering local economy. The economic growth outlook remains bleak and much needed foreign direct investment is hampered by our restrictive labour law, as well as concerns about Eskom’s ability to fuel an economic resurgence.

A silver lining to the dark economic cloud is that inflation in South Africa is under control, despite a weaker rand (which has a knock-on effect on imported goods, especially fuel prices). This creates the potential for further rate cuts by the Reserve Bank.

Unemployment in South Africa rose to a 16-year high of 29% in the second quarter of 2019. Stanlib notes that, on a trend basis, SA’s labour market continues to deteriorate. Fundamentally, this reflects the lack of fixed investment spending by the private sector, as well as sustained low business confidence. The high rate of unemployment contributes to much of the social tension, inequality and anguish experienced daily, especially among the youth. Increasing employment must be the number one economic/political/social objective and can only be resolved meaningfully through a concerted and

sustained effort to improve skills development, as well as encourage private sector fixed investment spending, business development and entrepreneurship.

It’s a long road that lies ahead, but at the very least, the Ramaphosa administration has turned efforts into the right direction.

Market performance

Most markets softened towards the end of the month as concerns about the global trade war and a relatively more hawkish stance from the Federal Reserve weighed on emerging markets and currencies. Gone is the hope of a trade war resolution, which we had just a month ago, and as the gloves came off again, the US Dollar strengthened against most other currencies.

The yield on the US 10-year treasury remained stable after it dipped below 2% for the first time since 2016. In the first few days of August, it fell by about 0.25% as it reflected concerns about global (and essentially US) growth. The negative global backdrop, as well as a credit rating update by Fitch, pushed South African bond yields slightly higher during the month.

South African equities struggled in July after somewhat of a recovery in June, and the broad FTSE/JSE All Share index ended the month 2.4% lower. Financial and resource stocks gave up in excess of 5%, with industrial counters adding a little over 1%.

Listed property just about gave up its June gains while gold and platinum both edged higher during the month.

The Rand struggled against the US Dollar (as did most other currencies around the globe) and continued this trend as it gave up more than 7% in two weeks after reaching a 6-month low on 18 July. '

South African Multi-Asset High Equity Funds delivered an average of 2.5% to investors during the last 12 months with their low equity counterparts ending 5.9% higher.

Commentary – The Inescapable International Trilemma

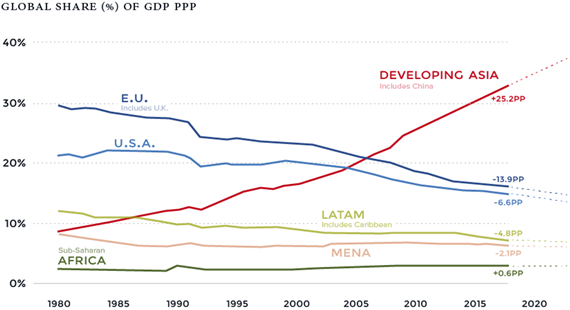

Much has been documented about the benefits to global economic growth that the globalisation of trade has had over the last four decades. In short, it has boosted economic output (the estimate is that NAFTA has contributed an additional 0.5% per annum to US economic output alone), and from a regional perspective it’s significantly strengthened Asia’s contribution to global economic activity:

It’s clearly this trend that, among others, drives the implementation of trade tariffs that the Trump administration has been initiating in recent years. Free trade agreements have many advantages aside from boosting economic activity. It can also lead to lower government spending, foreign direct investment and a technology transfer from multi-national firms to local employees.

The biggest criticism of free trade agreements is that they are responsible for job outsourcing. Other disadvantages include the theft of intellectual property, poor working conditions and reduced tax revenue (the latter often being addressed by the introduction of trade tariffs, even if proven to generally be ineffective).

Clearly a more open global economy had great advantages. In its current form, it has however created a populistic backlash which has resulted in the election of global leaders who are very keen to put national interests before those of the global population. Can this dilemma be solved? Can a democratic country be fully integrated into the global economy while it retains its national sovereignty?

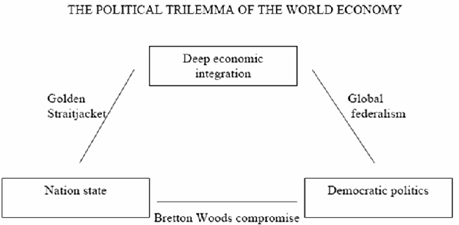

In his paper “How Far Will International Economic Integration Go?” Dani Rodrik argues that sometimes simple and bold ideas help us see more clearly, a complex reality that requires nuanced approaches. He has an "impossibility theorem" for the global economy that is like that. It says that democracy, national sovereignty and global economic integration are mutually incompatible: any two of the three can be combined, but one can never have all three simultaneously and in full. Here’s his theorem in a picture:

To see why this makes sense, note that deep economic integration requires that all transaction costs traders and financiers face in their cross-border dealings, are eliminated. Nation-states are a fundamental source of such transaction costs. They generate sovereign risk, create regulatory discontinuities at the border, prevent global regulation and supervision of financial intermediaries, and render a global lender of last resort a hopeless dream. The malfunctioning of the global financial system is intimately linked with these specific transaction costs.

So how can this be addressed?

One option is to go for global federalism (the European Union project is a regional version of this), where the scope of (democratic) politics is aligned with the scope of global markets. Realistically, though, this is something that cannot be done at a global scale. It is difficult to achieve even among a relatively like-minded and similar countries, as the experience of the EU demonstrates.

Another option is to maintain the nation state, but to make it responsive only to the needs of the international economy. This would be a state that would pursue global economic integration at the expense of other domestic objectives. The nineteenth century gold standard provides a historical example of this kind of a state. The collapse of the Argentine convertibility experiment of the 1990s provides a contemporary illustration of its inherent incompatibility with democracy.

Finally, we can downgrade our ambitions with respect to how much international economic integration we can (or should) achieve. So, we go for a limited version of globalization, which is what the post-war Bretton Woods regime was about (with its capital controls and limited trade liberalisation). It has, unfortunately, become a victim of its own success. We have forgotten the compromise embedded in that system, and which was the source of its success.

Rodrik maintains that any reform of the international economic system must face up to this trilemma. If we want more globalisation (and as a result more global wealth), we must either give up some democracy or some national sovereignty. Pretending that we can have all three simultaneously leaves us in an unstable no-man's land. Against this backdrop, it would perhaps be prudent to not expect a sudden end to the global trade war.

It’s partly the instability created by this trilemma that’s fuelling uncertainty in global investment markets. It’s also where opportunities lie for the shrewd investor. Globalisation (and a very easy monetary and fiscal environment) arguably provided a decade long tailwind for index investing. Perhaps this sea change will be the trigger for astute active managers to earn their keep again…

Source : APS Monthly Economic Commentary